The San Francisco Standard

Aug. 1, 2023

Kevin Truong

It’s become trendy to compare San Francisco’s recent woes to those of Detroit circa a decade ago, when a grim spiral of fleeing residents and social problems like drugs and crime led to the city’s near-collapse.

Plenty of podcasts, columns and social media posts have made the case, while others have dismissed the notion.

Here’s the comparison, in broad strokes: A city dominated by one industry undergoing major shifts and subsequently challenged by high vacancy and crime concerns leads residents to flee along with tax revenues, which in Detroit’s case led to the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history in 2013. Whole blocks of the once-thriving Midwestern city were abandoned as Detroit went from 1.85 million people in 1950 to 630,000 today.

These days, though, Detroit is steadily climbing its way back.

The former home of the U.S. auto industry—more synonymous with urban rot in recent years—has defied the most dire predictions for its failure. Its finances have stabilized, and basic services like garbage and streetlights have been restored. Pockets of development are sprouting.

Any honest analysis of the two cities notes their many key differences, but that doesn’t mean San Francisco can’t learn some lessons from Detroit and its recovery in recent years.

Downtown Recovery

Urban policy group San Francisco Bay Area Planning and Urban Research Association (SPUR) led a trip to the Motor City in May to do just that. Sujata Srivastava, SPUR’s San Francisco director, said the group decided to visit Detroit to study how it managed to stage a revival through a combination of public, private and philanthropic dollars.

“It’s just a really interesting example of how you come back from a major structural shift economically,” Srivastava said.

Some of the problems that factored into Detroit’s financial woes included irresponsible borrowing by city leaders and a lack of fiscal discipline during its downturn.

“They didn’t shrink their budget. They didn’t make some of those tough decisions early enough to be able to reverse the situation which caused their bankruptcy,” Srivastava said, noting the failed effort by Detroit leaders to tax their way out of a deficit.

“There’s probably something to learn from that in San Francisco,” she added.

Amid a growing budget deficit from lower-than-projected tax revenues, San Francisco recently passed a budget with record spending.

Downtown San Francisco’s pandemic recovery has been hampered by record-high vacancy rates, declining commercial property values and a series of prominent retail closures that have left the city’s core business district feeling distinctly hollowed out.

Pedestrians pass vacant retail stores on Powell Street in San Francisco on May 13, 2023. Jason Henry, The Standard

Downtown Detroit, on the other hand, has seen a renaissance that turned the formerly neglected area into a regional destination for arts, sports and entertainment. The city particularly excelled in organizing programming and events downtown geared toward both locals and tourists, like the Movement Electronic Music Festival.

“It’s hard to imagine where you would have that kind of experience in Downtown San Francisco,” Srivastava said.

One idea she posed for San Francisco was a designated area that was closed to cars, had a high density of bars and restaurants and could function as an experiment in redefining the neighborhood as an entertainment destination.

“There’s generally been a receptiveness to the idea of entertainment, arts and culture, but we need to get the state there and locals on board,” Srivastava said.

A number of philanthropic and private stakeholders stepped in to help kick-start Detroit’s turnaround and create a sense of place in its downtown. These actors were aided by public-sector incentives and had long-term commitments in the city.

One key example is Bedrock Real Estate, a company founded by billionaire Dan Gilbert and now led by former real estate developer Kofi Bonner.

Bedrock has invested more than $5 billion in downtown Detroit, starting with turning historic buildings into new homes and offices. The investments aimed to build communities where residents were no more than a 20-minute walk away from amenities and services.

One contrast to the Bay Area that Srivastava noted was how Detroit’s civic leaders, philanthropists and residents held a shared belief in the connection between the health of the city’s economic core and surrounding neighborhoods. That has led to more direct investments in Detroit’s recovery, in contrast to San Francisco’s relatively scattershot efforts.

Detroit’s approach may be something of a tough sell in San Francisco, which has a long history of conflict between Downtown business interests and surrounding neighborhoods. But, as local leaders have emphasized, business activity Downtown is key to San Francisco’s ability to fund itself, as well as the larger public perception of the city’s overall health.

One strategy that San Francisco could adopt involves public-sector mechanisms to spur new investment and close financing gaps for Downtown redevelopment. In Detroit’s case, this took a number of forms, including tax abatements, tax incentive financing and forgivable loans.

In a situation where San Francisco commercial property values are rapidly declining, tax increment financing—known locally as Enhanced Infrastructure Financing Districts—might help finance conversions or redevelopment projects. This strategy freezes property tax revenue at base levels and allows future tax revenue through redevelopment to spur private investment.

Srivastava said when planning officials and Downtown leaders from cities including Detroit, Seattle and New York were in San Francisco recently for a visit, they were optimistic that the city was primed for recovery because of its raw ingredients. However, they were shocked by the sheer time it took to navigate the city’s bureaucracy.

“They felt like there was a lot of low-hanging fruit the city wasn’t taking advantage of,” Srivastava said.

One economic development tactic could be shifting energy to attract and retain larger firms in Downtown San Francisco and diversify the types of industry that can thrive in the city. Srivastava referred to a recent City Controller’s Office report that found San Francisco’s five largest companies contributed 24% of all business tax revenue.

“There’s going to be a lot of challenges in San Francisco getting people to accept the fact you do need to do some incentives,” Srivastava said. “In many ways in the city, we don’t have that muscle, and it really needs to be built very, very quickly.”

Housing Woes

Sarah Karlinsky, a senior advisor at SPUR focusing on housing and land issues, said she believes the comparisons to Detroit come from the anxiety that San Franciscans feel that this bust cycle might not see a boom on the horizon.

“There are precious few people who have in their memory what it feels like for San Francisco to sort of be on the precipice,” Karlinsky said.

In her particular area of expertise, however, San Francisco has been on the precipice for a long time. The lack of available and affordable homes has hampered the city’s ability to retain its diverse population and factored directly into its problems with homelessness.

In Detroit, she expected to find the opposite situation, where abundant housing meant far fewer housing challenges. Instead, she found a different type of housing crisis due to foreclosures and habitability issues.

Between 2005 and 2015, nearly a third of Detroit’s residential properties were foreclosed, the vast majority due to property tax delinquencies. Detroit’s property tax rate is more than double San Francisco’s.

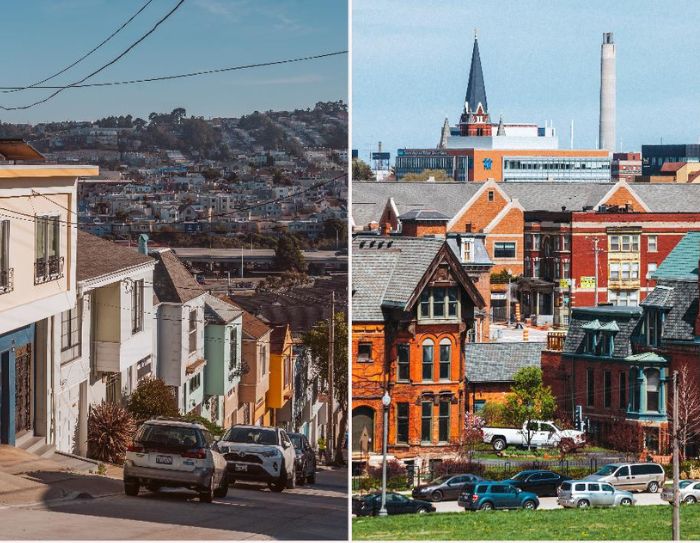

A composite image shows housing on Putnam Street in San Francisco’s Bernal Heights, left, and a view of homes in the Brush Park district in Detroit, right. Michaela Vatcheva for The Standard and Peter Viisimaa.

The difficulties in accessing credit and loans to refinance properties lead residents to live in dilapidated housing.

However, in contrast to the Bay Area, the abundance of homes in Detroit means street homelessness is less of a problem.

“Unsurprisingly, places that have a lot more housing tend to have fewer homeless people regardless of rates of poverty or mental health issues,” Karlinsky said.

Public-private partnerships have helped stabilize the housing stock and reduce foreclosures in Detroit. As part of a program called Make It Home, the city purchases homes prior to foreclosure and sells them to a nonprofit funded by philanthropic dollars. This group then works with residents to help finance the purchase of the home.

Although Detroit faces different housing challenges, one quality that particularly impressed Karlinsky was the alignment of philanthropy, business and the public sector.

“Everyone was rowing in the same direction in terms of concentrating resources around a set of agreed-upon problems,” Karlinsky said.

In her experience, that kind of agreement across sectors doesn’t exist in San Francisco. Karlinsky posited that the culture of collaboration may be partly due to the dire straits Detroit leaders faced navigating through its bankruptcy.

“Meanwhile, we have had this culture of abundance for so long,” Karlinsky said. “Part of that abundance means that we can fight about smaller things.”

Filling Vacant Storefronts

Katie Ettman, SPUR’s senior policy manager specializing in food and agriculture, said the comparison between San Francisco and Detroit falls apart when considering the scale of issues each city faces.

Take population loss, for example. Detroit’s current population is roughly a third of the size it was in the mid-20th century. More recently, San Francisco lost 6.3% of its population between 2019 and 2021—a larger dip than any two-year period in Detroit’s history.

However, while Detroit’s slide has continued through the decades, San Francisco’s population decline has slowed significantly in the last year.

A stated goal that San Francisco and Detroit have in common is to foster entrepreneurship, particularly among immigrants and people of color. Ettman said one lesson that San Francisco can learn from is creating steppingstones for small businesses to help them graduate into market-rate commercial spaces.

Eastern Market Detroit Kitchen Connect created scaled pricing that raises kitchen costs over a five-year period to give businesses time to scale and prepare to move into their own space.

People sit in the lobby of the Shinola Hotel in Downtown Detroit on July 8, 2023. Nick Hagen, Washington Post

In line with Detroit’s larger strategy around neighborhood building and placemaking, SPUR also researched programs that developed incubator kitchens for food businesses along with housing rehabilitation to create more “complete neighborhoods” with services and resources that didn’t previously exist.

As another example, Ettman pointed to Motor City Match, a nonprofit offering grants and technical assistance to small businesses. One of the unique aspects of the organization’s model is matching up entrepreneurs with commercial space that makes sense from a business and community perspective.

“I think it is just a real acknowledgment that space isn’t the only problem,” Ettman said. “If you plop in the wrong business into the wrong particular building or storefront, you’re not going to find success in the same way.”