Increasing Worker Wages

People need to earn more money to move into the middle class, Goss said.

Among other recommendations, DFC is calling for more jobs that put the city’s Black residents on a path to a middle-class income, increased support systems to encourage post-secondary certificate and/or degree attainment and efforts to help Black entrepreneurs scale the businesses they’ve started into bigger and more profitable enterprises.

Through its Detroit at Work workforce programs, the city is helping to build a bridge to get those who are unemployed or underemployed into jobs and, ultimately, on a path to the middle class.

“We have been very intentional about saying that we are here to support Black and Brown Detroiters in their economic mobility pursuits and that includes those who are disabled. That includes the justice-involved community, veterans and then, of course, the cultural community that have typically been underrepresented as well,” said Dana Williams, chief strategy officer for the city’s Detroit At Work workforce efforts.

The city is operating with an “A,B,C model” in its workforce development efforts, Williams said. “A” is getting Detroit residents into a job.

“There are some folks we know who need to go to work tomorrow, just to be able to get some immediate income. And so we’re connecting them with those opportunities,” she said.

For those who want to move into a better job, the city offers career coaches to connect them with over 50 training programs for high-demand, high-growth industries.

And then there are the people who may have a few skills but want to create new opportunities for themselves and to grow through a new middle-wage or management position or study area, she said.

“Maybe that’s getting them connected to a four-year college program, or a community college program utilizing the other resources that are here like Michigan Reconnect so that they can earn that wage, as well, and get truly a path to a long-term career,” Williams said.

The mayor has also been focused on attracting large employers like FCA-Stellantis (which is employing roughly 4,000, most of them Detroiters) and GM Factory Zero, the carmaker’s first, fully dedicated electric vehicle assembly plant, among other companies. Many of the positions at the plants would be considered middle-class jobs, said John Roach, media relations director for the city.

Increase of Households With Bachelor’s Degree or Higher

Black households with a bachelor’s degree or higher increased from 11% in 2010 to 16% in 2021.

Raising Education Access

Post-secondary education is important to position residents for a middle-income job. But only 14 percent of Detroiters have an associate degree or higher, Goss said.

The Detroit Regional Chamber has provided the Detroit Promise scholarship for the past decade to Detroit students to cover the costs of tuition for trade programs and certificates, and associate and bachelor’s degrees at 26 Michigan colleges. The program is aimed at helping the region achieve a 60 percent post-secondary attainment goal and to cut the racial equity gap in half by 2030.

Currently, more than 2,000 students are enrolled in Detroit Promise, with 500 new students enrolling in the program last fall, down from about 700 each of the two years prior, said Gregory Handel, vice president, education and talent for the Detroit Regional Chamber.

The drop has been entirely driven by enrollment declines at the community college level as students have opted for work instead of school, as wages for entry-level work went up, he said. Four-year university enrollment, however, has grown to about 400 students from 230 a year before the pandemic.

It was funded for its first seven years by the Michigan Excellence in Education Foundation, a partnership of business, foundation/nonprofit and government, with some additional funding from the Detroit chamber’s endowments. Over the last few years, funding responsibility has largely shifted to the Detroit Promise Zone Authority, which captures a portion of state assessed property taxes for education. But the foundation continues to fundraise for additional student programs, Handel said.

More recently, Wayne State University announced the WSU Guarantee to provide free tuition for Michigan students who attend the Detroit-based university.

Both programs provide “last dollar” support to eliminate tuition costs for eligible students by rounding out state and federal assistance.

Those types of programs are needed to increase access to post-secondary credentials and higher-paying jobs. But so, too, is the need to eliminate systemic racism preventing people of color from moving into well-paying jobs once they’ve attained post-secondary credentials, Goss said.

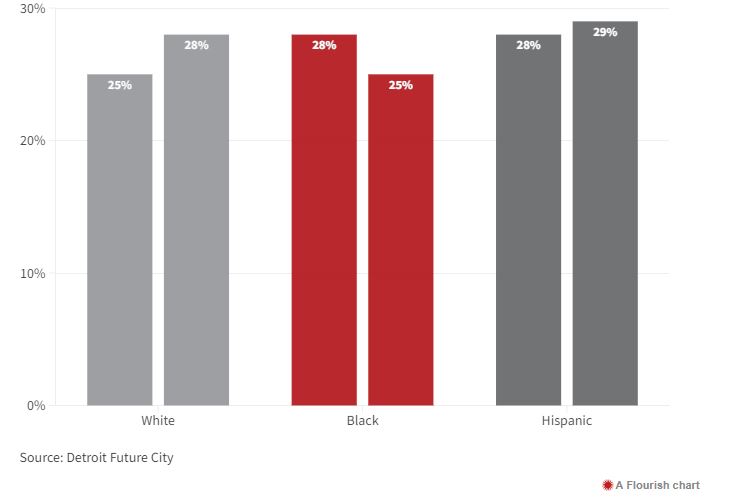

Black and Latino/Hispanic workers are employed in well-paying, fast-growing occupations at lower rates than their white and Asian counterparts, according to the Growth Occupations report DFC released last month with Brookings.

Attracting Companies

In its quest to bring new employers and more jobs to Southeast Michigan, the Detroit Regional Partnership has honed in on three growth sectors that could tap into the region’s talent base, President and CEO Maureen Krauss said: mobility, smart manufacturing, and corporate and professional services like banking and information technology.

Over the last year, DRP has attracted 33 companies to its 11-county footprint in Southeast Michigan, all in one of those three sectors, Krauss said. Nine of them are in Wayne County. Collectively, they’ve created roughly 5,000 jobs and over $2.4 billion in new investment.

“We have the right talent, supply chain and support for those companies to succeed here,” Krauss said.

“I think that bodes well for the future of the Black middle class in Detroit.”

The region has strong engineering and smart manufacturing talent and people who are experienced with working in a manufacturing environment.

Some manufacturing workers may need to upgrade their skills to work with new software or machines, Krauss said, “but if you have to train someone on a new piece of equipment, you’d rather have someone who’s worked in a factory before.”

Diversity of talent is also important for companies, and Detroit is authentically diverse. That’s a big advantage for the city and region, Krauss said.

It brought data analytics company Majorel to Detroit.

Majorel was looking for a diverse and skilled workforce, people who were comfortable working on the computer, databases and websites. They found what they needed in Detroit, with 60-70 percent of their hires from the city, Krauss said.

“It’s a global company, and they have a really good career path for people who work for them … to get to that middle class.”

Encouraging Startups, Entrepreneurs

Support for Black entrepreneurs would also help move more of the city’s residents into the middle class, DFC’s Goss said.

“In other cities, entrepreneurship is a direct pathway to wealth. (But) not here in Detroit,” she said.

Black and Brown business owners are not receiving the access to capital, and they’re not growing, she said.

“I’m not just talking about startup capital; I’m talking about investment in existing businesses … . There are more of those smaller startups than there are anything else in Detroit.”

Detroit at Work has teamed up with Wayne County Community College to offer an entrepreneurship training academy, a two-week program providing aspiring entrepreneurs a basic primer so they can decide if they want to move forward in starting their own business, Williams said.

The city has also provided entrepreneurs with support since 2015 through Motor City Match. To date, it has provided $11.4 million in grants to 1,696 businesses.

Another program, Detroit Means Business, was developed during the height of COVID to help struggling small businesses stay afloat during the lockdowns, to reopen and, now, to thrive, Johnson said.

“What we do know is that entrepreneurship leads to wealth generation,” he said.

Beyond city-led and other efforts, the New Economy Initiative, a foundation-funded economic development effort housed at the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan, is working to increase access to support for early entrepreneurs and to create a system for second-stage entrepreneurs looking to scale, said President and CEO Wafa Dinaro.

Boosting Safety Efforts

Economic mobility is one part of growing the city’s Black middle class. Keeping Black middle-class families in the city by ensuring it’s a place they want to live is the other.

“Safety is at the core of everything,” DEGC CEO Johnson said.

In his State of the City address in early March, Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan announced plans to invest $10 million over the next two years in efforts to reduce neighborhood crime. The program will give neighborhood groups up to $700,000 a year to create and fund programs to reduce violence. If the programs are successful, they could be extended.

It builds on earlier efforts like Detroit Ceasefire, a collaboration between local neighborhoods and local police to prevent gang violence.

Families want walkable neighborhoods, diverse housing options, quality schools, good grocery stores and safe parks and other community gathering spaces. They want they want to be able to let their kids walk, run and play without any problems, said Goss, who lives in the Villages on Detroit’s east side.

That’s a big lift, given that many of the suburban amenities they want are missing in Detroit’s neighborhoods, she said.

“People don’t want to be locked into neighborhoods that aren’t improving, where everyone is poor and the neighborhood looks really bad,” she said.

“The neighborhoods that don’t look like that … you can’t afford them unless you’re really well, well above what we think of as the middle class.”

The higher cost of city taxes also means a $60,000 annual salary doesn’t go as far toward purchasing a higher quality of life in Detroit versus Eastpointe or Southfield, Goss said.

The city administration and others such as the Kresge Foundation and Live6 Alliance, in northwest Detroit, and Rocket Community Fund and the Gilbert Family Foundation more broadly are working to, among other things, improve neighborhoods.

Early Education Plays Important Role

Good schools are also part of the picture.

With the Black middle class in mind, Detroit Public Schools Community District has been making investments for the past five years in its specialty, application schools (focused on areas like foreign languages, aviation, science and medicine, and fine and performing arts) and examination schools, which require prospective students to take an exam to be considered for admission and provide rigorous college- and career-prep education, Superintendent Nikolai Vitti said in an emailed statement.

It has earmarked funding to rebuild Cody and Pershing high schools, opened two Montessori programs, he said, and restored Martin Luther King Jr. High as an examination high school, where students must take an exam to be considered for admission and then receive rigorous college and career preparation, among other programs.

The district’s partnership in the cradle-to-career educational programs on the former Marygrove College campus is also attracting Black middle-class families back to traditional public education, as is the Detroit School of the Arts, Vitti said.

“Lastly, we believe that our expansion of Pre-K with certified teachers will also attract middle-class families to DPSCD where families can avoid tuition at private schools and still receive a high-quality early learning experience.

“We know that the expansion of all of these programs has led DPSCD’s Detroit market share of school-aged children to increase versus the decline of city charter schools since the pandemic.”

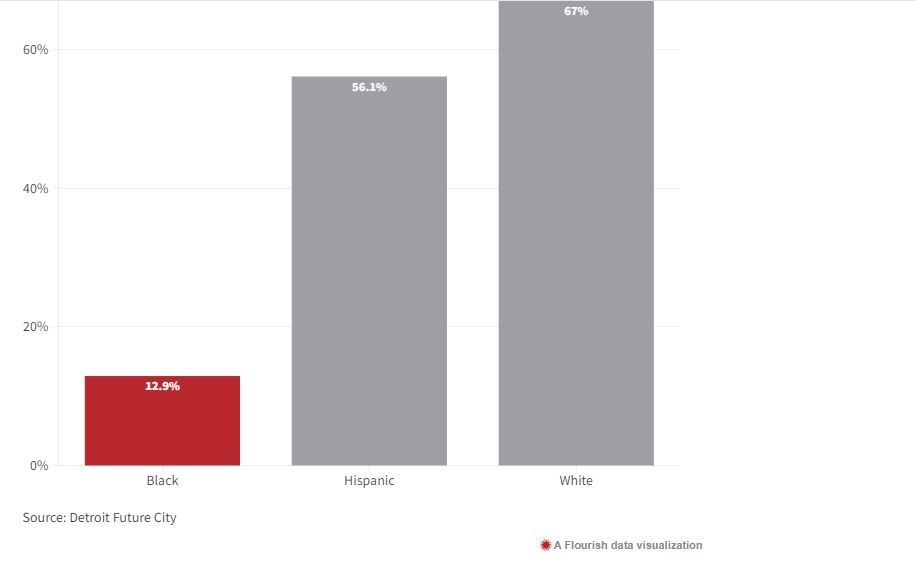

Homeownership Rates

Putting it All Together

It’s been a real community effort to address the issues Detroit Future City has raised, said Laura Grannemann, executive director of the Rocket Community Fund and Gilbert Family Foundation. Community development organizations, nonprofits, the Kresge Foundation, JPMorgan Chase and many others have been working, in consultation with Detroit Future City, to address the issues that have been raised as critical to growing the city’s Black middle class.

“It certainly has to be the work of the community. It can’t just be one organization,” she said.

For their part, in March 2021, the Rocket Community Fund and Gilbert Family Foundation announced a 10-year, $500 million philanthropic investment to build economic opportunity in Detroit neighborhoods, with a focus on stabilizing the housing of low-income Detroit families at risk of displacement, then following up with targeted investments focused on public life and economic mobility.

The two funders are doing that by providing funding to prevent tenant evictions and tax foreclosures and providing wealth-building opportunities through homeownership and assistance for home repair investments to ensure people want to stay in their homes, she said.

They are also creating entrepreneurship opportunities for Detroiters and are focused on workforce development through efforts like the Motor City Contractor Fund, which is supporting local BIPOC contractors to expand their businesses at a time when there is unprecedented level of contractor opportunities in the city, Grannemann said.

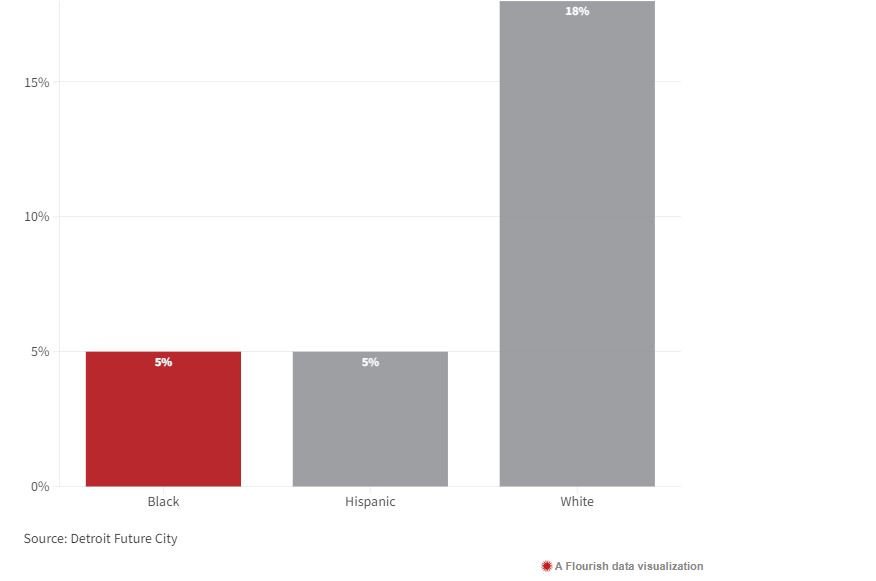

Mortgages to African Americans for Homes in Detroit

“And then, of course, one thing that unfortunately too often gets overlooked is creating those strong social bonds and connections to the neighborhoods through things like public space opportunities and connection to arts and culture,” she said.

The $500,000 Thriving Neighborhoods Fund is providing support for about 20 grassroots organizations across the city that are activating public spaces and bringing programming to their neighborhoods. In some cases, it is an investment in something like markets in public spaces around the city.

“We’ve also invested in parks around the city,” like Curtis Jones Park, in collaboration with Northwest Goldberg Cares, Grannemann said.

“There is a fantastic and thriving neighborhood, but they just did not have a space where they could go to be super active to have kids … play basketball and go ice skating and interact with local entrepreneurs.”

Now, they do.

The city of Detroit has a long history of Black homeownership and of diverse communities that are led by Black leaders, Grannemann said.

“Unfortunately, we started to see that slip away just a little bit with the announcement a couple of years ago, where it was going from a majority homeowner (city) to a majority renter city.”

“Through the efforts of a lot of people, ourselves included, we’ve been able to see that trend turn back, but it’s so important for Detroit — really, the beacon of the Black middle class and, honestly, the founder of the Black middle class in many ways — we need to ensure that we keep that level of focus on inclusion and equity and opportunity to, again, not just live here, but really thrive here.”